The many faces of climate change in Virginia

In a state as diverse as Virginia, so are the climate impacts - and the approach to covering them.

Written by Sean Sublette

In the modern media environment, bringing stories forward about the warming climate can be challenging. Getting beyond basic talking points and focusing on impacts to different communities across Virginia helps explain the growing impact on the Old Dominion — from the mountains to the coast.

The most obvious may be along Virginia’s waterfront, whether it is the rural Northern Neck or more urbanized Hampton Roads. For much of Virginia’s coastline, water has risen between 1-2 feet over the last century, and while the impacts may not be immediately obvious, they are showing up more frequently.

Rising sea level from the warming climate threatens the country’s coastal military infrastructure based in Virginia, with the most glaring example being Naval Station Norfolk — the largest naval base in the world.

Too often, rising sea levels are only mentioned when we see video of a house falling into the ocean — like on the nearby Outer Banks. But of greater impact is the rising water on the inland bays and tidal rivers of Virginia, and we need to remind people that the water is all connected.

Sea level rise also means that water is climbing higher into individual neighborhoods of Hampton Roads away from the oceanfront. Tidal flooding that used to be negligible is now reaching into people’s backyards.

Source: Climate Central

Parks and infrastructure are at increasing risk, and perhaps more viscerally, it is a complicating factor on areas such as Riverside Memorial Park, a century-old cemetery along the Elizabeth River in Norfolk.

Higher sea level also brings up the water table and the salinity lines along the western shores of the Chesapeake Bay, impacting farming communities on the Middle Peninsula and the Northern Neck. Higher salinity levels introduce more difficulties for farmers, and for day-to-day living, septic systems in these locations may no longer be able to function.

As heavy rain becomes more intense, risks from flash flooding continue to rise, whether that be in the urban areas of Richmond and Northern Virginia or the rural landscapes in the deeper valleys west of the Blue Ridge. Most of us remember the devastating flash flooding in the Southwestern Mountains in 2022.

Much like Hampton Roads, the underlying geography makes these valleys susceptible to flooding, but additional heavy rain from a warming climate heightens the risk. In turn, this hits people in their wallets from rising insurance rates. Virginia only needs to look at the headlines coming from Florida to see how the insurance industry is coming to grips with the additional risks to property.

Then there is the heat itself. As summers tend to get hotter, there is more heat related illness risk — especially to outdoor workers, whether they are farm workers in Virginia’s rural piedmont or construction workers helping build the blossoming areas of Fredericksburg and Petersburg.

The flip side is winter. Admittedly, we may enjoy milder winters compared to a couple of generations ago, but it also means the frost-free season is getting shorter. As a result, more insects — like mosquitoes and ticks — survive over the winter. On top of that, the allergy season starts earlier and lasts longer.

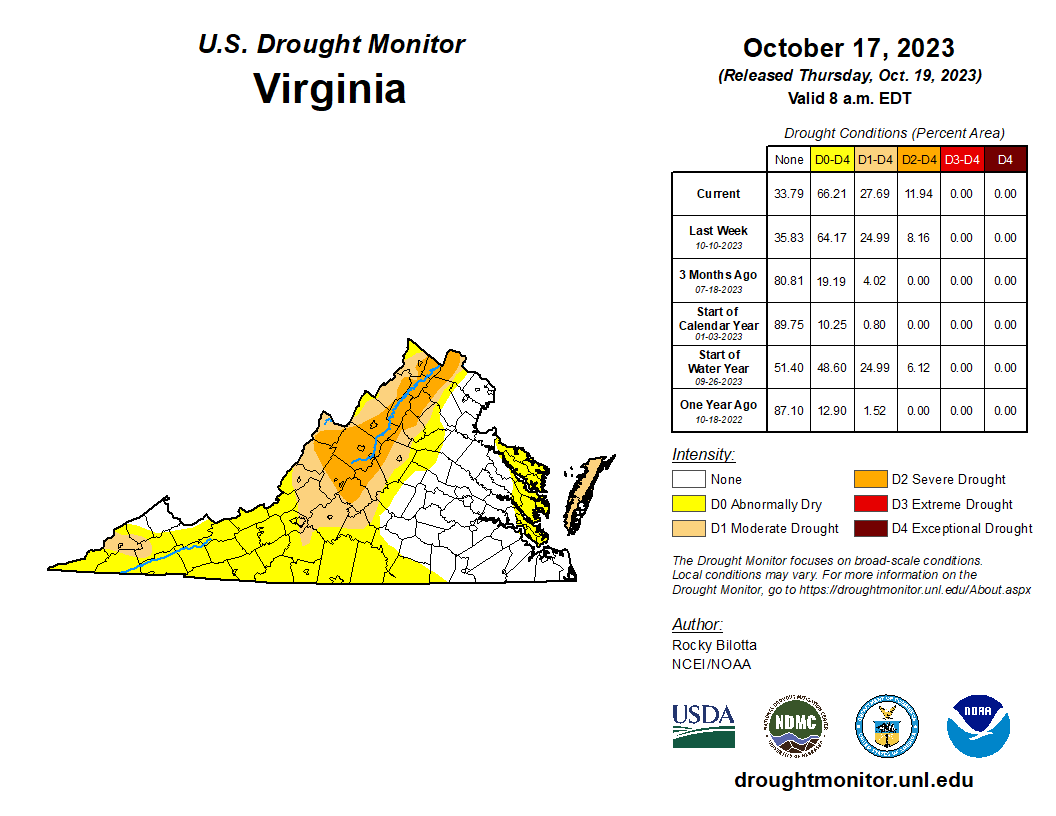

Our humid climate makes droughts less common than in the western part of the country, but they are more impactful as the soils dry out more quickly in the hotter summers. The Shenandoah Valley continues to deal with drought this fall, and the apple orchards in the northwestern part of the state have been struggling.

Source: US Drought Monitor

The key to coverage is finding stories where people live who are being impacted. Sharing someone’s personal story about an environmental impact goes a long way in helping an audience understand how climate change is also impacting them, or will impact them soon.

Sharing solutions and positive stories also keeps everyone from sliding down the dark hole of doomism. More than $1.12 million was allocated in 2022 via Virginia’s involvement in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) to help stabilize the shoreline at Riverside Memorial Cemetery in Norfolk. The same pool of funds last year provided $2.23 million to decrease the risk of flash flooding to people, property, and infrastructure in Dickenson County. Numerous other projects are being funded from Covington to the Chesapeake.

But money from RGGI is at risk.

So no matter where you live in the Commonwealth, or how you cover it, being in touch with how climate is impacting the people living here is crucial now and in the years to come.

Author

Sean is Chief Meteorologist for the Richmond Times-Dispatch and specializes in severe weather and climate communications.